by Bonnie Ross Meador.

Joshua Burnett Ross, named for his maternal grandfather, was born in Jackson Township, Clermont County, Ohio, in 1842. He was the first of eleven children born to Osmore L. and Jerusha Loveland Burnett Ross, who had been married in Jackson Township on April 14, 1839.

In the 1850s Osmore Ross moved his family to Clark County, Illinois, where he had purchased farm acreage at auction for $200. (Total interest on the mortgage was $20.) The Rosses lived on the outskirts of Casey and Crooked Creek, not far from Hazel Dell. According to the 1860 Illinois census, Joshua Ross, then 17, was a chair maker.

We have come to realize, however, that family history is much more than merely extracting a few facts from official records. Our passion for it grew out of reading The Red Badge of Courage as children and wanting to make a connection to our past through the War Between the States. It was this hope that led us on our quest.

The bits and pieces collected through family anecdotes, newspaper stories, and photographs were elusive to trace, since the family has roots in Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Minnesota, Utah, Oregon, California, Washington, North Carolina, and Texas. We could find nothing on Joshua beyond the 1860 census. Then I remembered The Red Badge of Courage, and a new adventure unfolded. With notebook, camera, and filing cabinet in tow, we traveled to Clark County, Illinois, to get a more authentic feeling for the family by walking in their footsteps, touching their gravestones, and walking around the old homestead. But there was still no Joshua . . ..

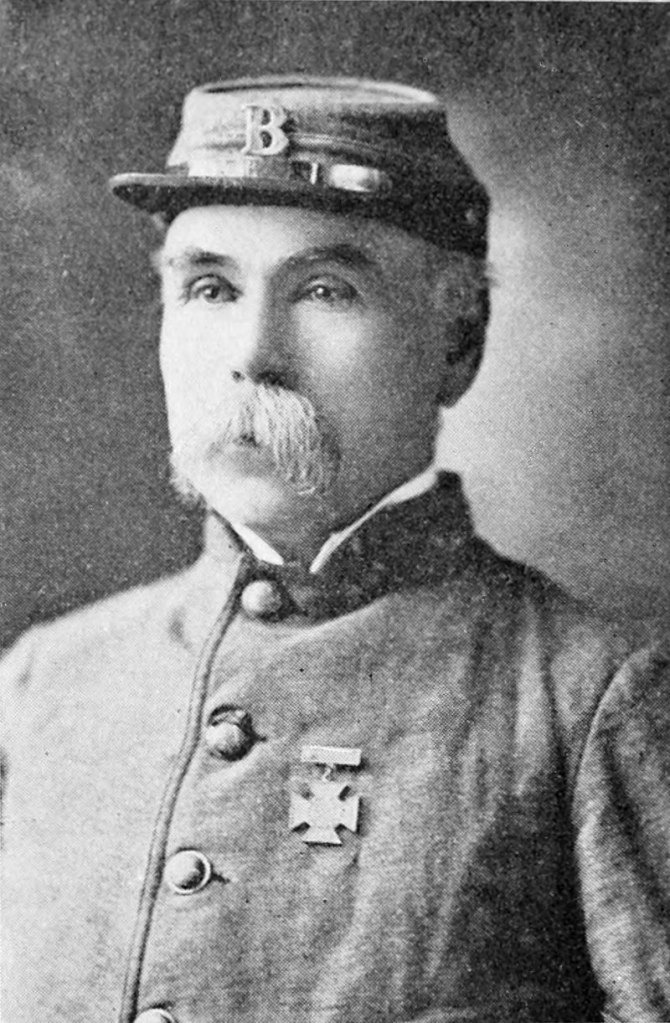

With the help of a librarian from Greenup, Illinois, and after days of internet research, Joshua began to emerge from the shadows. Records showed that the young chair maker had joined the Federals and become a Union soldier: on June 28, 1861, he mustered into the 21st Illinois Infantry, Company H, in Mattoon, Illinois, a few miles from his home.

Joshua’s first commanding officer was Colonel Ulysses S. Grant; when Grant received his promotion from the President, he was replaced by Colonel John W. S. Alexander. The 21st fought valiantly at Perryville, Kentucky, and at Stones River, near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where the regiment was assigned to General Rosecrans. We were amazed to find that on their march to Stones River, the 21st had camped on Dumont Hill in Scottsville, Kentucky, the town where we presently reside.

The National Archives forwarded the information that Joshua had been wounded in the upper left chest area during the Battle of Stones River, December 1862. He was transferred to U.S. General Hospital #19, in the Morris and Stratton Building on Market Street– now 2nd Avenue–in Nashville, where he died of his injuries on February 22, 1863. Joshua Burnett Ross was buried in grave 3634 in a temporary cemetery located near the hospital. His remains were later moved to Section E, Grave 0730, in the Nashville National Cemetery.

Jerusha Ross filed for her son’s pension on June 30, 1880, seventeen and one-half years after his death. Joshua’s brother, Silas L. Ross, named one of his sons after him: that child, Joshua Burnett Ross, was my grandfather.

Engraved on a brass plate near the arched marble gateway of the National Cemetery are the words of Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address,” a fitting tribute to my great-great-uncle and all who lie beside him. On July 4, 2004, a hot Sunday afternoon, armed with advice from the Nashville Historical Newsletter and its readers, we were able to walk directly to Joshua’s grave. Knowing he was from a poor farm family who lived far away, we had little doubt that we were the first family members to stand at his gravesite. Our visit to the National Cemetery, the close of a great adventure, brought us a step closer to knowing where we came from. Our lives are made richer by the knowledge that my great-great-uncle gave up his life for us and for the hope of an America undivided.