Primary Source Document, transcribed by Debie Cox, author of Nashville History blog.

Editor’s Note: Historian Debie Cox discovered the Jennings will in the Metro Archives in 2001. Jennings’ tragic death soon after he drew it up gives unusual poignancy to the document. The will is historically significant because it is likely the oldest surviving document from Nashville, other than the Cumberland Compact itself.

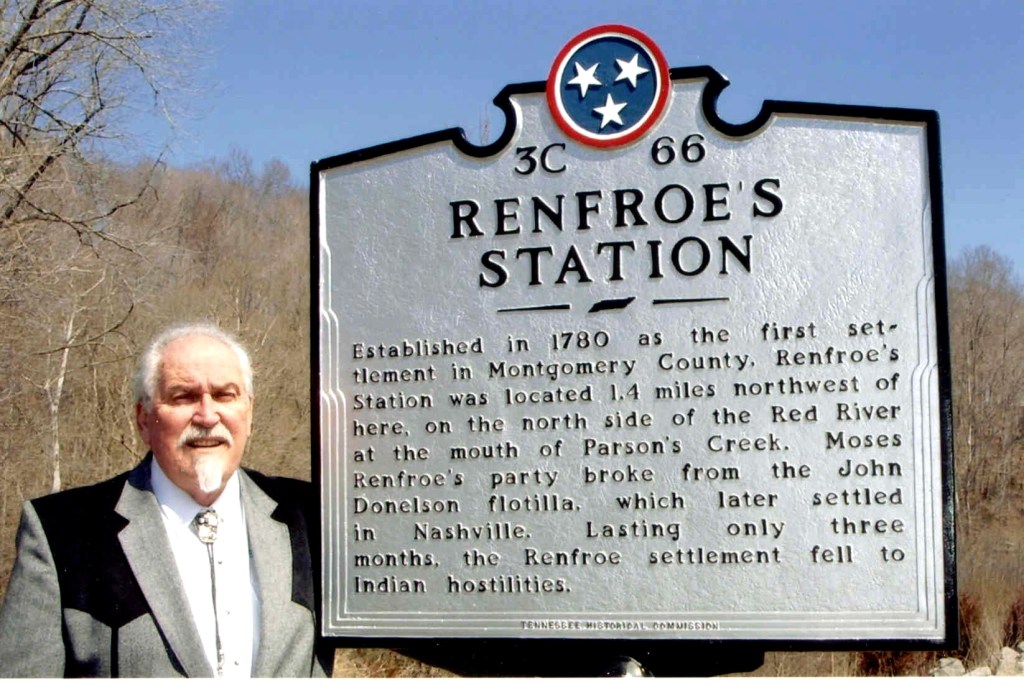

Jonathan Jennings and his family were among the group of pioneers who journeyed with the John Donelson flotilla to the Cumberland Settlements. Donelson recorded in his journal on March 8, 1780, that Indians had attacked the flotilla, and that the Jennings family had been left behind as the settlers in the other boats made their escape.

The Jennings boat had indeed survived, but not without casualties. Jennings’ daughter Elizabeth, wife of Ephraim Peyton, had given birth the day before the attack. In the confusion of the fighting, her baby was killed. Jonathan Jennings Jr., son of the elder Jennings, had jumped from the boat along with two other men. Although young Jennings, who was probably in his early teens, and one of the others made it to shore, the third man drowned. Jennings Jr. and his companion were quickly captured by the Indians, who scalped Jennings and killed the other man. Young Jennings, who had survived his injuries, was eventually rescued by a trader who agreed to pay his ransom, and he was later able to reunite with his family in the Cumberland Settlements. After the attack, the remaining members of the Jennings family had continued on their journey, arriving at Fort Nashborough on April 24, 1780.

According to J. G. M. Ramsey in his Annals of Tennessee, Jonathan Jennings Sr., was himself killed by Indians three or four months later, in July or August 1780. He left an undated will, which was presented to the Davidson County court in July 1784 and proven on the oaths of James Robertson and William Fletcher. The will had also been witnessed by Zachariah White, who had died at the Battle of the Bluffs near Fort Nashborough in April 1781. The signatures of Jennings, Robertson, and White can be verified through comparison with their signatures on the Cumberland Compact, which all three men had signed in May of 1780. The will reads as follows:

In the name of God Amen I Jonathan Jennings of North Carolina on Cumberland River having this day Received several wounds from the Indians and calling to mind the mortality of my Body do make and Ordain this to be my last will & Testament And first of all I give and recommend my soul to God that gave it and my body to be disposed of at the Discretion of my executors And as touching my Worldly affairs I dispose of them in manner following Viz

Item I give and bequeath to my It is my Desire that my Estate be Equally divided between my Wife my sons William, Edmond, Elizabeth Haranor Mary Aggy Anne & Susannah all but such a part as shall be hereafter disposed of

Item I give and bequeath to my son Jonathan who was Scalped by Indians and rendered incapable of getting his living a Negrow girl Milla & her increase who is to remain with my beloved wife till my son comes of age Also a Choice Rifle Gun & a Horse and Saddle Item I give my beloved wife Four Choice Cows and Caves The Wards Milla and her increase and the Ward Jonathan being interlined I devise that my Loveing Wife and my son Edmond be Executrix & Executor of this my last Will & Testament

Signed Sealed & Published in Presents

of Jonathan Jenings

Zach White

Js. Robertson

William Fletcher