by Dave Price.

Although several researchers have written parts of the story, a comprehensive history of Nashville’s theaters has not yet been written. Nor will that ponderous task be undertaken by this scribe; but as we approach the year 2000, it might be of interest to look briefly at the local theater scene as it existed a century ago, with a few comments on the later history of our turn-of-the-century theaters.

Four venues could be classified as theaters in the Nashville of 1900, two that were built as such and two others that had been adapted to serve the purpose: the Grand Opera House, the Masonic, the Vendome, and the Union Gospel Tabernacle, often simply called “the Auditorium.”

The oldest of the four would be the Grand Opera House at 431 North Cherry Street (today’s Fourth Avenue), whose entrance was not far from the present-day entrance to the former Municipal Auditorium. The Grand had opened July 1, 1850, as The Adelphi, amid much publicity, spoken of as one of the finest playhouses in the South. This theater operated under many names and managements as the Nashville, the Gaiety, May’s Grand, Milsom’s, and possibly others. By 1900 it had been occupied for six years by the Boyle stock company, Tony J. Boyle, proprietor, presenting occasional vaudeville shows.

The next in age would be the Masonic. The Old Masonic Hall at 422 Church Street – that is to say, on the north side of Church behind the Maxwell House – had been rebuilt in 1859-1860 to include a theater, which over the years had been called Jenny Wilmore’s, the Bijou, the New Masonic, and finally, toward the end of the nineteenth century, simply the Masonic. In 1900 it was under the very capable management of William A. Sheetz, who was also a long-time fixture at the Vendome. Before long, Mrs. Boyle of the Grand would take over management of the Masonic and announce that she was booking “shows that have been shut out of the syndicate,” a reference to the Vendome’s use of the attractions of Klaw and Erlanger, a New York booking and management concern with a secure grip on much of the dramatic theater business of the day.

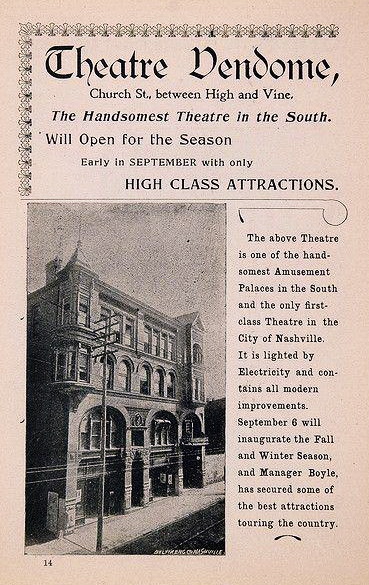

The Vendome – facing the Capitol from the south side of Church midway between High and Vine – had opened October 2, 1887, as a truly first-class playhouse. One of the stockholders was J. Oliver Milsom, who was to manage the Vendome for a time and, as mentioned above, briefly gave his name to the Grand when he managed that theater.

These three locations primarily showed “legitimate theater,” that is to say, dramatic productions or plays. Vaudeville had had a somewhat sporadic presence locally, and moving pictures had not yet come to Nashville. (However, their arrival was not far off: the Vendome was trying out “Vitagraph Matinees” by late 1901, and in 1902 the Grand began showing “Biograph Views”)

The story of the Union Gospel Tabernacle is well known, and we shall not repeat it here. Suffice it to say that it was erected on Summer Street (now Fifth Avenue) just north of Broad by a local group under the leadership of riverboat magnate Tom Ryman after his conversion by noted evangelist Sam Jones. Not until Ryman’s death in 1904 was the building called Ryman Auditorium, but by 1900 it was being called “the Auditorium” and was advertising lyceum programs, which term may need some explanation to today’s readers. The lyceum was somewhat related to the traveling Chautauqua movement, except that it took place indoors rather than in tents. An auditorium could book a series of programs of a more-or-less educational nature which varied from temperance lecturers and choral groups to the occasional play or operatic production, or which might even include such a novelty performance as that of a very refined magician. De Long Rice, a later manager of the Auditorium, managed a bureau of lyceum attractions at the same time and frequently booked his clients at the Auditorium.

The Vendome burned in 1902. An interesting sidelight to the fire is that manager Billy Sheetz attempted to lease the Masonic, by then under Mrs. Boyle’s management, for the attractions he had booked for the Vendome, but she turned him down. The Auditorium subsequently offered to let the attractions play there . . . but only under their own management. The managers of the next few Sheetz-booked shows took the position that their contract with Sheetz was voided when his theater burned. Some then played the Masonic, and others appeared at the Auditorium on their own terms, cutting Sheetz out of the picture! Not one to overlook a snub, the scrappy Billy Sheetz reopened the Vendome before the end of 1902 with a guaranteed hit: Al G. Field’s Minstrels.

After the Grand also burned in 1902, the Boyle stock company moved to the Masonic, taking the name of the Grand along with them. The Masonic promptly began to be called the Grand (or on occasion the “Little Grand”). In 1904 a new theater, the Bijou, would be erected on the former Grand site by Jake Wells, an enterprising sort who, among other things, once managed the Birmingham Barons, a Chicago Cubs farm team.

Older readers may recall the Bijou, which in 1916 became one of the South’s leading theaters for African American audiences, and which lasted until it was demolished during the winter of 1957-1958 for the construction of the Municipal Auditorium.

The new Grand (Masonic) was vacated for theatrical purposes in 1914, and the property was sold in 1915 to Joe Fensterwald, who demolished the building and erected the steel and concrete edifice that was to house Burk and Company. The fiction that Burk’s occupied the former Masonic building has been repeated too many times (even in print!) for us to convince anyone otherwise at this late date. The Masonic lodge moved to a new location on Seventh Avenue North, where many of us recall the majestic lions guarding its portals. It stood next to the Clarkston Hotel and behind the War Memorial Building.

In 1920 the Vendome became Loew’s Vendome (or as time went by simply “Loew’s”) and presented both moving pictures and vaudeville shows. Several years later Loew’s entered into an agreement with movie king Tony Sudekum whereby his Princess Theater down the street became the only “vaude” house in town and Loew’s got the pick of the first-run movies.

Loew’s burned again in 1967 and this time was not rebuilt, a signal that the Church Street of our youth was disappearing. For years thereafter one could walk through the old Loew’s lobby to the parking garage that occupied the site of the theater auditorium. In the mid-1980s all that was wrecked for the building of Church Street Center, and you saw what happened to that!

You will read elsewhere that the Ryman was Nashville’s only playhouse after the Vendome became Loew’s, but those reports ignore the importance of the 1910 Orpheum, which booked dramatic roadshows for most of its almost thirty years. Parenthetically, we should also mention what older Nashvillians already know: namely, that during the Depression the Edward Bellamy Players went broke at the Orpheum, and Mrs. Inez Bassett Alder bought the props and wardrobe for the Hume-Fogg dramatic department. The Ryman, of course, is the only survivor of our 1900 quartet and is again presenting live stage attractions as these lines are being penned. (1999)