by Kathy B. Lauder.

Born near Lynchburg, Virginia, on August 19, 1840, Marcus Breckenridge Toney came to Tennessee with his family when he was two years old.1 His father, a millwright, had intended to settle in St. Louis, but Mrs. Toney became too ill to travel beyond Nashville.2 She never recovered her health and died when Marcus was six. None of Toney’s siblings survived childhood and, when his father died early in 1852, the eleven-year-old found himself alone in the world.3 Relatives took him back to Virginia, where he attended college, but by 1860 he had returned to Nashville.4

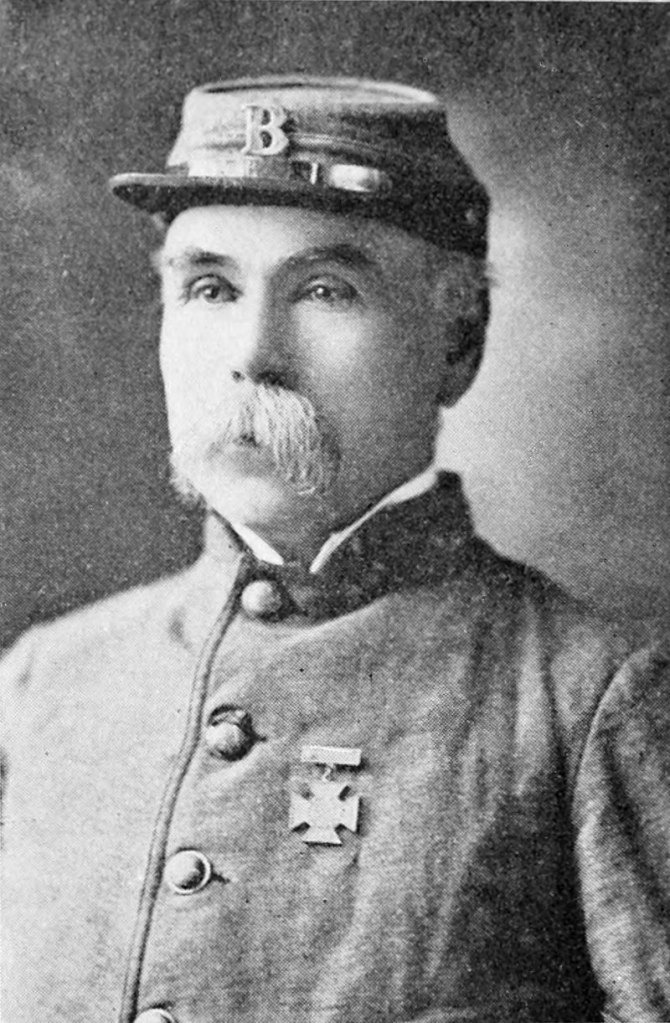

When war broke out, Toney enlisted in the First Regiment of the Tennessee Infantry (Feild’s), Company B, known as the Rock City Guards.5 The regiment was sent to Virginia, where they fought beside Lee at Cheat Mountain and Stonewall Jackson at the Potomac River before returning to guard the Cumberland Gap.6 In 1862 they took part in Bragg’s invasion of Kentucky and fought at Stones River in December.7 Toney was transferred in February 1864 to the Forty-Fourth Virginia Regiment, which participated in the Battle of the Wilderness in May.8 Captured with 1100 other Confederate soldiers, he was sent to the prison camp at Point Lookout, Maryland,9 and then transferred to Elmira, New York,10 where he spent the remainder of the war. His experiences as a prisoner make up a significant part of his memoir, The Privations of a Private*, published in 1906.

Returning to Nashville, Toney became involved for a short time with the Ku Klux Klan, perceiving the group as “conservators of law and order”11 during the chaotic years following the war. On December 4, 1868, Toney was on board the steamer United States when it crashed into the steamer America in the Ohio River.12 He escaped by swimming to shore in his nightclothes. Many other passengers who jumped into the river to escape the burning ship died as flaming oil spread across the water.13

In 1872 Toney married Miss Sally Hill Claiborne, who would bear him two children. The same year he became Nashville commercial agent for the New York Central Railroad, holding that position more than forty years.14 He wrote many articles for newspapers and other publications, particularly the Confederate Veteran, edited by his friend Sumner Cunningham. Toney was a witty and amusing raconteur and was frequently invited to speak about his wartime experiences.

During the mid-1880s Marcus Toney and Dr. William Bumpus became interested in establishing a residence for the widows of members of the Masonic brotherhood. The two men traveled throughout Tennessee seeking financial support for the project, and their board acquired a charter of corporation in August 1886.15 The Masonic Widows’ and Orphans’ Home was constructed near Nashville on 220 acres donated by Col. Jere Baxter.16 Funded by the Grand Lodge and personal donations, the home and its associated dairy farm opened in 1892 and operated successfully until the 1930s.

Marcus Toney died of “old age” 17 in Nashville on November 1, 1929, and was buried in Mt. Olivet Cemetery. (2014)

*A paperback edition of Privations of a Private, edited by Dr. Robert E. Hunt of MTSU, was published by Fire Ant Books in 2005. That and other editions of the book are available from most booksellers.

SOURCES:

1 Hale, Will Thomas, and Dixon Lanier Merritt. A History of Tennessee and Tennesseans: The Leaders and Representative Men in Commerce, Industry and Modern Activities, Volume V. Lewis Publishing Company, 1913, 1507.

2 Hale and Merritt, 1508.

3 Toney, Marcus B. The Privations of a Private. Edited by Robert E. Hunt. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005, xi-xii.

4 Hale and Merritt, 1508.

5 “Soldier Details,” U. S. National Park Service: The Civil War. http://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-soldiers-detail.htm?soldier_id=788cd8d9-dc7a-df11-bf36-b8ac6f5d926a Website accessed April 26, 2014.

6 “Regimental Organisation.” First Regiment, Tennessee Infantry (Maney’s) Co. E. http://first-tennessee.co.uk/organisation.htm Website accessed April 26, 2014.

7 “Regimental Organisation.”

8 Toney, 64-70.

9 Toney, 76-83.

10 Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume XXIX. Edited by Robert Alonzo Brock. Richmond, VA: Southern Historical Society, 1901, Chapter 1-19.

11 Toney, 118.

12 “Ohio River Tragedy.” Northern Kentucky Views. http://www.nkyviews.com/gallatin/gallatin_river_disasters.htm Website accessed April 10, 2014.

13 Toney, 120-121.

14 Hale and Merritt, 1508.

15 “The Masonic Widows and Orphans Fund of Tennessee.” The Grand Lodge of Tennessee, Free and Accepted Masons. http://www.grandlodge-tn.org/?chapters=Y&page=WO Website accessed April 20, 2014.

16 “Masonic Widows’ and Children’s Home.” Historic Nashville. http://historicnashville.wordpress.com/2009/03/05/masonic-widows-childrens-home/ Website accessed April 20, 2014.

17 Tennessee Death Records, 1908-1959, Roll #11. Nashville: Tennessee State Library and Archives.