by Carter G. Baker.

Buried near each other in the same lot on Oak Avenue are brothers-in-law John Patton Erwin (1795-1857) and Thomas Lanier Williams (1786-1856). Their relationship was not always so peaceful. Erwin, two-time mayor of Nashville (1821 and 1834), was married to Thomas’s sister, Frances (Fannie) Lanier Williams (1796-1872). Fannie is buried at Mt. Olivet with her daughters who lived to adulthood. Four other children who died young are presumed to be buried at City Cemetery with their father.

Both Erwin and Williams left significant marks on Tennessee history. John Patton Erwin was a newspaper editor, lawyer, banker, justice of the peace, and postmaster of Nashville. He was also the secretary of the Robertson Association, which was deeply involved in the American settlement of Texas while that region was still part of Mexico. His sister Jane’s first husband was wealthy Nashville banker, Thomas Yeatman, under whom Erwin served for a time as cashier. (Their son, Thomas Yeatman Jr., was a powerful supporter of the Confederate cause.) After Yeatman’s death Jane married the Hon. John Bell, Speaker of the House of Representatives, U.S. Senator, and Union Party candidate for president in 1860.

Erwin’s brother married one of Henry Clay’s daughters, while his cousin, also named Jane Erwin, was married to Charles Dickinson, who died in a famous duel with Andrew Jackson. Dickinson’s remains, recently discovered, were moved from a long-unmarked grave near Whitland Avenue to Nashville City Cemetery on June 25, 2010.

Thomas Lanier Williams was a lawyer, state representative and senator, and a justice on the State Supreme Court. His most lasting contribution to Tennessee was his long period of service as Chancellor of Tennessee, during which he became known as the father of equity law in the state. Less well known is the role he played many years earlier in the historic victory of the Tennessee Volunteers at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in the War of 1812. He and his wife’s uncle, Hugh Lawson White (an 1836 candidate for president), convinced his brother Col. John Williams (later a U. S. senator) to lead the 39th U. S. Infantry Regiment in bringing desperately-needed supplies and manpower to Col. Andrew Jackson. Jackson would give Williams and his soldiers great credit for their pivotal role in defeating the British-allied Creek Nation at the Horseshoe. This important battle set the stage for Jackson’s success in the Battle of New Orleans and insured that Britain would never control the lower Mississippi River or the valuable ports of Mobile and Pensacola.

Unfortunately, John Williams and Jackson later became political enemies, while Sam Houston, who had carried the regimental flag (designed by Thomas’s wife, Polly McClung Williams) in the successful charge at Horseshoe Bend, remained close to Jackson. Houston wrote a vitriolic letter to President John Quincy Adams urging him not to appoint John Patton Erwin as postmaster. Adams did make the appointment, but Erwin challenged Houston to a duel over the matter. Although the duel never actually took place, Houston wounded Erwin’s second.

Sometime in the 1820s John Patton Erwin declared bankruptcy, perhaps because of unsuccessful land speculation. Col. Joseph Williams, Fannie Erwin’s father, dispatched his son, Thomas Lanier Williams, to Nashville to protect his daughter’s interests and to make certain that Fannie’s future inheritance was specifically shielded from her husband. Although this decision caused some animosity at the time, matters were eventually smoothed over.

The Erwins’ home from 1831-1860 was named “Buena Vista.” The house was located on the hill near Rosa Parks Avenue and I-65, where the St. Cecilia motherhouse now stands. Thomas Lanier Williams stayed with the Erwins on many of his trips between his Knoxville residence and Nashville, and he eventually died in their home.

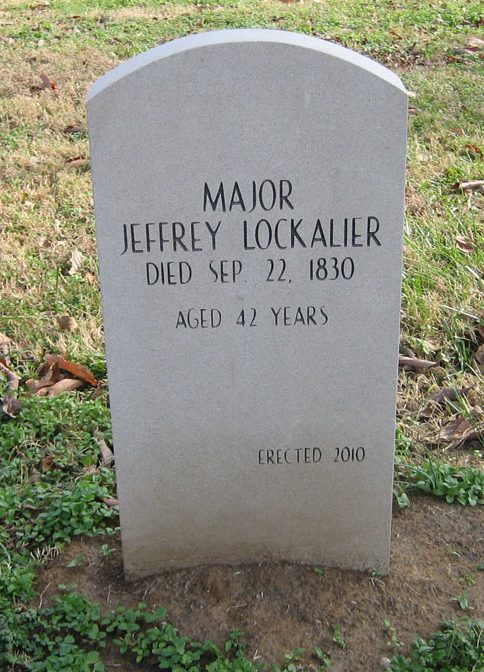

John Patton Erwin’s grave in City Cemetery is marked with a Nashville Mayors’ gravestone, while Thomas Lanier Williams is honored with a V.A. marker reflecting his military service in the War of 1812.

Thomas Lanier Williams was the namesake of four other men named Thomas Lanier Williams. The most famous of these was playwright “Tennessee” Williams, a several-times-great-nephew of Thomas I and a great-great grandson of Colonel John Williams.

The flag of the 39th, still owned by a descendant of Colonel Williams, is on temporary display this spring at the Tennessee State Museum’s War of 1812 “Tennessee Volunteers” exhibit. (2012)

Previously published in Monuments & Milestones, the Nashville City Cemetery Newsletter.