by Dave Price.

Our original market house was completed during 1802 and can be seen in the well-known map of 1804 Nashville, which appeared in Clayton’s History of Davidson County, Tennessee. Its replacement was begun in April 1828 and was occupied in January 1829. This structure, shown on the 1831 J.P. Ayres (Doolittle & Munson) map, consisted of a long market shed running north and south with a two-story building at each end.

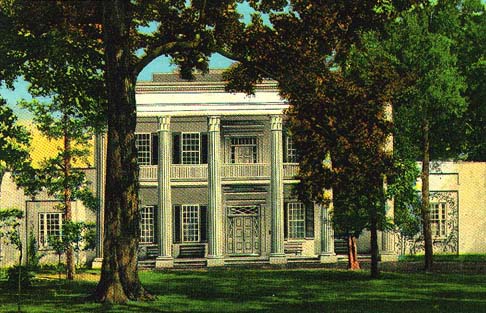

The Ayres map was surrounded by a number of drawings of local buildings and scenes, so we know what the southerly building looked like. It was the “Tennessee Lottery Office,” the image of which has been reproduced, although I am unable to cite such a copy in one of the standard histories. Interesting features of this Lottery Office are a recessed arch shape in the brick on the west side of the building and round windows in the upper corners of the south end.

A “salt print” (dated ca. 1856) of the west side of Nashville’s Public Square attracted a good deal of attention a few years ago when the State Museum purchased the rare item at a Sotheby’s auction. (We old Nashville buffs had been aware of a copy negative in the state archives for years.) The print reveals the same features mentioned above in the northwest corner of the northerly building, indicating that the matching original end buildings of the market house were still in place with some modifications: single story wings added to the south (and we presume north) sides of the end buildings and a cupola added to the roof of the south building (and probably to the north one as well, although it cannot be seen in the print).

A familiar photo taken from Capitol Hill a few years later shows that the end buildings had either been extensively remodeled or replaced with much larger three-story structures having two square towers on each end building. This image is reproduced in Adams-Christian, p. 53. Since the old Methodist Publishing House is shown, the picture must date from before 1873. The southerly building at some point became the City Hall, and Creighton tells us that the Supreme Court met in one of the buildings for a time and that 100 stalls existed in the market section or long connecting shed.

A good view of the southerly building can be seen in James Patrick’s Architecture in Tennessee, 1768-1897, where it is suggested that Adolphus Heiman may have remodeled the buildings “about 1855.” Despite the estimated dates, the “ca. 1856” image was obviously made prior to the “about 1855” remodeling. Incidentally, this building is shown in Max Hochstetler’s great Opryland Hotel mural, which can be seen on the cover of the Summer 1990 Tennessee Historical Quarterly. A view that shows both end buildings and the connecting market building is seen in Jack Norman’s The Nashville I Knew, p. 125.

Although not mentioned by any of the histories that I consulted, the southerly building was consumed by the Burns Block fire on the square during the night of January 2, 1897. The fire company stopped at the site of an old cistern between the Court House and the Market House but found it had been Macadamed over. During the delay in finding a new water source, the old dilapidated City Hall was engulfed in flame and the crowd shouted, “Let it burn!” which is exactly what happened.

This fire was responsible for the replacement of the City Hall with the large 1898 building that older readers will recall (Norman has a good view of this on p. 122 and an unusual architectural drawing is found in the photo section of Fedora Small Frank’s Beginnings on Market Street).

In the meantime the northerly building still had at least one of its towers in an 1892 photo but had lost both towers by 1910. This building contained the office of the Market Master and such city offices as those of the Meat and Dairy Inspectors and was generally called simply, “the north end.” The new City Hall remained much the same, although much of its one large tower was gone by the time of its 1936-37 demolition. The March 14, 1933, East Nashville Tornado caused some damage on the square and this may have been when the tower was shortened.

Aerial photographs taken during the construction of the present (Woolwine) Court House show that, while the market house section and the northerly building were razed along with the Strickland Court House (since they lay in the path of construction), the City Hall was actually a few feet south of the new building and was the last part to fall. It is also obvious from these photos that the market section had been widened considerably over the years; it contained 114 or more stalls by the time of its demise.

The later (1937-1955) Market House stands today behind the present court house and is still in use as the Ben West Building, or more commonly the “Traffic Court Building.” The once-familiar wagons are gone, and the farm trucks that once surrounded the Court House moved north of the Capitol to the new Farmer’s Market in 1955. That market has now been replaced and will no doubt be recalled by a later generation as “the old Farmers’ Market.” (1998)