Part Four: 1961-1965.

1961 Jan In Selma, Dallas County, Alabama, more than 80% of the African-American population live below the poverty line, and less than 1% of eligible blacks are registered to vote.

1961 Feb Nine young African-American men are jailed in Rock Hill, South Carolina after staging a sit-in at a McCrory’s lunch counter. They are the first to use the “jail, no bail” strategy, which will lighten the financial burden of civil rights groups across the country. The tactic also keeps cities from profiting from the arrests of civil rights protesters, who further contend that paying bail and fines indicates acceptance of an immoral system and validates their own arrests.

1961 May 4 Organized by members of SNCC, the Freedom Rides will test the enforcement of Boynton v. Virginia. The first bus of thirteen Freedom Riders (7 blacks, 6 whites) leaves Washington, D.C. In Rock Hill, South Carolina, their first stop in the Deep South, two men (one is John Lewis, who will later become a U.S. Congressman) are beaten by a white mob.

1961 May 14 One of the Freedom Riders buses is burned in Anniston, Alabama. As a second bus pulls into the Trailways Station in Birmingham, riders are attacked and badly beaten by a mob of Ku Klux Klan members. Sheriff Bull Connor orders Birmingham police to stay away. The wounded Freedom Riders eventually escape to New Orleans when Attorney General Robert Kennedy orders a plane to take them there.

1961 May 17 Unwilling to allow the KKK to defeat them, Tennessee activists take a bus from Nashville to Birmingham; Bull Connor arrests them and dumps them by the side of the road, just over the Tennessee border. They make their way back to Birmingham, but they cannot find a bus driver willing to risk driving them any further.

1961 May 20 Under orders from Robert Kennedy, the Alabama governor provides a Highway Patrol escort, and the bus roars toward Montgomery at 90 mph. At the city limits the police guards disappear, under Bull Connor’s orders, and the riders are set upon and brutally beaten by a mob of KKK supporters, who have as much as 20 uninterrupted minutes to attack the Riders with bats and iron bars before the police arrive and drive the growing mob away with teargas. Many riders are left bloody and unconscious, including reporters (the mob has quickly destroyed the cameras) and Justice Department official John Seigenthaler, who is found lying unconscious in the street. Local black citizens eventually rescue the wounded and take them to hospitals.

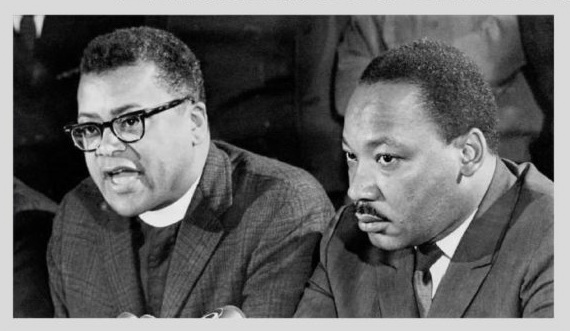

1961 May 21 Martin Luther King and James Farmer of CORE (who is already recruiting more Freedom Riders) speak to 1200 people in Rev. Ralph Abernathy’s Montgomery church, while a mob outside throws rocks at the windows, overturns cars, and starts fires. Over the next several days, more Freedom Riders arrive; most are jailed. By the end of the summer, more than 60 Freedom Rides have come south, and more than 300 individuals have been jailed, including many local supporters of the Riders.

1961 Winter The Loyola University (Chicago) basketball team puts four black players on the floor at one time, breaking an unwritten rule of college sports.

1962 Darryl Hill is recruited by coach Lee Corso at the University of Maryland. He is the first African-American football player in the Southwest Conference (SWC). The only black player on the team until his senior year, he sets two receiving records that stand for decades.

1962 Sep 30 James Meredith is escorted onto the University of Mississippi (Oxford) campus by a convoy of Federal Marshals. In the riots that follow, two people are killed and many others injured.

1963 Jan Alabama Governor George Wallace declares, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

1963 Apr 8 Sidney Poitier is the first African American to win the Academy Award for Best Actor. Starring in three major films, he is also the top box office star of the year.

1963 Apr 16 Jailed for his protest activities, Martin Luther King writes his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” which quickly becomes a classic document of the Civil Rights struggle with its assertion that individuals have a moral right to disobey unjust laws.

1963 May Civil rights activists, including children, march in Birmingham. By the end of the first day, 700 have been arrested. When 1000 more youngsters turn out to march peacefully on May 3, Commissioner of Public Safety Bull Connor turns police dogs and high-pressure fire hoses on them. Within five days, 2500 are in jail, at least 80% of them children. After 38 days of confrontation and public outcry from across the nation, Birmingham city officials and business leaders agree to desegregate public facilities. Governor George Wallace’s refusal to accept the plan will lead to violent confrontation.

1963 Jun 11 Governor George Wallace stands in the doorway of Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama, blocking the enrollment of two black students. Later, confronted by Federal Marshals and Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach, he stands aside.

1963 Jun 12 NAACP activist Medgar Evers is shot to death outside his home in Jackson, Mississippi. His assailant, KKK member Byron De La Beckwith, will not be found guilty of his murder until 1994.

1963 Jul 26 The true fulfillment of Executive Order 9981 (1948)—equality of treatment and opportunity for all military personnel—requires a change in Defense Department policy, which finally occurs with the publication of Department Directive 5120.36, issued fifteen years to the day after Truman’s original order. This major policy shift, ordered by Secretary of Defense Robert J. McNamara, expands the military’s responsibility to eliminate off-base discrimination detrimental to the military effectiveness of black servicemen.

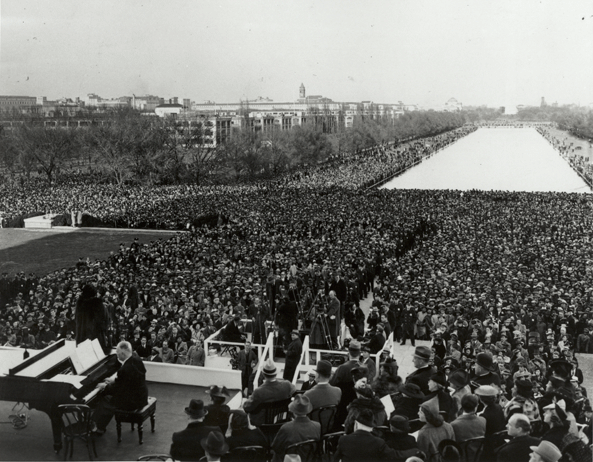

1963 Aug 28 250,000 civil rights supporters take part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The highlight of the event occurs when Martin Luther King Jr. delivers his “I Have a Dream” speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

1963 Sep Voter registration volunteers in Selma, Alabama, face arrests, beatings, and death threats. Thirty-two black schoolteachers who attempt to register to vote are fired by the all-white school board. After the September 15 church bombing, students begin lunch counter sit-ins – 300 are arrested, including John Lewis of SNCC.

1963 Sep 15 Four young girls, ages 11 to 14, are killed when a bomb explodes in the basement of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Many other people are injured.

1963 Nov 22 President John F. Kennedy is assassinated in Dallas, Texas. Lyndon B. Johnson becomes President.

1964 Jan 3 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. is Time Magazine’s Man of the Year.

1964 Jan 23 The 24th Amendment abolishes the poll tax, employed in Southern states since Reconstruction to make it difficult for poor blacks to vote.

1964 Jun 14 Freedom Summer (also called the Mississippi Summer Project) begins with training sessions in Ohio. This effort to register black voters, mostly in Mississippi (in which only 6.2% of eligible blacks were registered to vote) is spearheaded by SNCC, along with the NAACP, CORE, and the SCLC. Dr. Staughton Lynd, a history professor at Yale University, directs the Freedom Schools project.

1964 Jun 21 Three young civil rights workers – James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman – are arrested in Neshoba County, Mississippi. and then disappear.

1964 Jul 2 President Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The law prohibits discrimination of all kinds based on race, color, religion, or national origin; it also provides the federal government with the authority to enforce civil rights legislation. To Johnson’s dismay, the passage of this law will be followed by a year of violence as white supremacists attempt to undo any gains in registering black voters. Johnson turns his attention to passing a Voting Rights act.

1964 Aug 4 The bodies of James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman are found, buried in an earthen dam. Schwerner and Goodman have been shot; Chaney was beaten to death. The state of Mississippi refuses to charge anyone with the murders. Seven people are eventually tried for Federal crimes, but none will serve more than six years in jail.

1964 Aug 25 By the end of the 10-week Freedom Summer project, four workers have been killed, four others critically wounded, 80 beaten, and 1000 arrested. Thirty black homes or businesses and 37 churches have been bombed or burned. Many of these crimes are never solved. Since Mississippi still requires a literacy test for voter registration, of 17,000 Mississippi blacks trying to register, only 1,600 succeed.

1964 Oct 14 Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., 35, becomes the youngest person ever to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. He will deliver his powerful acceptance speech on December 10 in Oslo: “Nonviolence is the answer to the crucial political and moral question of our time – the need for man to overcome oppression and violence without resorting to violence and oppression.”

1964 Nov Archie Walter (A. W.) Willis Jr. is elected to the Tennessee General Assembly. When he takes his seat in January 1963, he becomes the first African American to serve in the Tennessee House of Representatives since Reconstruction.

1965 Feb 18 Jimmie Lee Jackson, 26, is shot during a peaceful protest in Marion, Alabama, as he tries to protect his mother and grandfather from a beating by Alabama State Troopers. Jackson, shot at very close range, dies a week later. An Alabama Grand Jury refuses to indict James Bonard Fowler, the trooper who shot him. (See May 10, 2007.)

1965 Feb 21 Black nationalist leader Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little in Nebraska in 1925) is assassinated during a speech in Manhattan. Three members of the Black Muslim organization are accused of his murder.

1965 Mar 7 SCLC leader James Bevel organizes a 55-mile march from Selma, Alabama, to the state capitol in Montgomery – a demonstration on behalf of African-American voting rights. On the outskirts of Selma, just after crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the 600 marchers are brutally assaulted, in full view of TV cameras, by heavily armed state troopers & deputies. ABC interrupts its broadcast of Judgment in Nuremberg, a Nazi war crimes documentary, to show footage of the violence. John Lewis, 25, and the Rev. Hosea Williams, 39, leading the march are clubbed to the ground, as are many others. A widely-published photograph shows 54-year-old Amelia Boynton Robinson lying unconscious on the bridge. Fifty marchers are hospitalized. The event will come to be known as “Bloody Sunday.”

1965 Mar 9 Martin Luther King leads a second march across the Pettus Bridge. The marchers kneel in prayer, then turn back around, obeying the court order that prohibits them from going on to Montgomery. After the march, three white ministers are attacked and beaten – one (James Reeb, from Boston) dies in Birmingham, after Selma’s public hospital refuses to treat him. On the same day, demonstrations condemning “Bloody Sunday,” as the March 7 incident has come to be called, take place in 80 cities across the nation.

1965 Mar 15 President Lyndon B. Johnson makes what most consider his greatest speech to Congress as he calls for a Voting Rights bill: “It is wrong—deadly wrong—to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country . . .. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and State of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.”

1965 Mar 16 A Federal judge rules in Williams v. Wallace: “The law is clear that the right to petition one’s government for the redress of grievances may be exercised in large groups . . .. These rights may . . . be exercised by marching, even along public highways.” Granting the protesters their First Amendment rights to march also means the State of Alabama can no longer obstruct them.

1965 Mar 21 Nearly 8,000 people, of all races, begin the third march from Selma to Montgomery. The 5-day march covers a 54-mile route along the “Jefferson Davis Highway”(U.S. 80). Protected by 4,000 troops (U.S. Army, FBI agents and Federal Marshals, and the Alabama National Guard under Federal command), the marchers average around ten miles a day and will finally arrive at the Alabama Capitol building on the 25th.

1965 Mar 23 The marchers pass through cold, rainy Lowndes County, where, although African Americans make up 81% of the population, not one is registered to vote, whereas the 2240 white registrants on the voting rolls constitute 118% of the adult white population!

1965 Mar 25 Martin Luther King speaks to the marchers in Montgomery (“How Long, Not Long”) and they are entertained by Harry Belafonte, Tony Bennett, Peter, Paul & Mary, Sammy Davis Jr., and others in a “Stars for Freedom” rally.

1965 Apr Fannie Lou Hamer and other SNCC members help found the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union to organize cotton workers.

1965 May 19 Patricia Harris becomes the first African American since Ebenezer Bassett (1869, Haiti) to serve as an American ambassador (Luxembourg).

1965 Aug 6 President Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This bill, urgently sought by Johnson, along with Dr. King and other Civil Rights leaders, eliminates such devices as poll taxes and literacy tests, and it authorizes federal registrars to register qualified voters.

1965 Aug 11 A large-scale race riot begins in the Watts area of Los Angeles, sparked by a traffic arrest. As community leaders try to restore order, rioters block fire-fighters from burning buildings, and vandalism and looting take place throughout the area. Nearly 14,000 National Guardsmen are sent in to help restore order. By the time the violence ends six days later, 34 people have been killed, 1,032 are injured, and 3,952 are arrested. Nearly 1,000 buildings have been damaged or destroyed, and the city is left with $40 million in property damage.

1965 Sep 15 The first episode of the television series I Spy is broadcast. This is the first drama series on American television to feature a black actor (Bill Cosby) in a starring role.

1965 Sep 24 President Johnson issues Executive Order 11246, which requires government contractors to “take affirmative action” toward prospective minority employees in all aspects of hiring and employment.

Adapted from a timeline created by Kathy B. Lauder for the TN State Library and Archives, 2013.