by Terry Baker.

The Nashville street that connects Church Street with West End Avenue was known as Richland or Harding Pike in 1881 when Ed Buford built a house there and called it “By Ma.” He gave the house that folksy name because it was situated next to Burlington, the estate then owned by Elizabeth Boddie Elliston, Buford’s mother-in-law and widow of W.R. Elliston. As a result of the 1904 changes in street names, Elliston Street became 23rd Avenue North, and Richland was renamed Elliston Place.

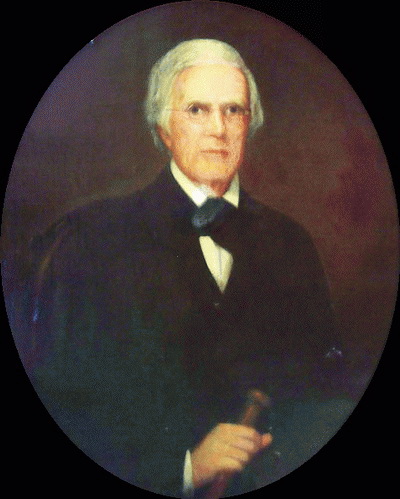

A look at the 1889 Nashville City Atlas gives us some idea of the extent of the Elliston holdings, which included land now occupied by Vanderbilt University. At 23rd and Elliston Place the AT&T building now fronts where “By Ma” once stood. Burlington went up just to the west in two stages, first when former mayor Joseph Thorp Elliston bought the land in 1821 for just under $11,500. When he died in 1856 his youngest son, W.R. Elliston, inherited the property. William F. Strickland, the architect who designed the State Capitol, drew up a plan for the “new” Burlington, at least according to Elliston family lore. Strickland died in 1854, but a floor plan drawing he is said to have made for Burlington has survived.

Though not strictly historical, family legends can augment dates and surviving maps. Stories recorded in Burlington: A Memory, published in 1958 by Josephine Elliston Farrell, make the house the scene of several interesting anecdotes of the Civil War. One of W. R. Elliston’s daughters, Louise, is the star of most of the tales, but the most poignant story concerns Willie, Elliston’s youngest son. At the age of five he was taken into custody on the almost laughable suspicion of being involved in espionage. His father was able to secure his release, but not before Willie’s shoes had been cut apart and his clothing searched.

Both Joseph T. Elliston and his son W.R. were slaveholders. W.R. sided with the Confederacy and is even said to have enlisted in 1861, but he was at home in 1862 when Burlington was taken over by the occupying Federals. The family legends tell us of skirmishes on the property and of a wounded Confederate spy hiding out in the house.

The names of W.R. Elliston’s daughters read like a Who’s Who of European royalty. Maria Louisa, usually called Louise, was twenty-three when she married Dr. L.P. Yandell in 1867. Research indicates that he had been a surgeon in the Confederate Army. Josephine married Norman Farrell in 1869. A freshman at Columbia University in New York when the war broke out, Farrell booked passage for Cuba, was put ashore in Florida, and eventually joined Forrest’s cavalry.

Of special interest is the youngest, Lizinka, born in 1851. Her namesake was the widow Lizinka Campbell-Brown, herself named after the Czarina of Russia. In 1875 Lizinka Elliston married Ed Buford, another Confederate veteran.

W.R. Elliston died in New York City on July 4, 1870. He and his wife Elizabeth had traveled there to seek a specialist’s advice on his abdominal pains. In a bureaucratic irony stemming from the rules governing the census, he was enumerated on the day of his funeral. Buried with him that same day was Medora Thayer Elliston, the eleven-month-old daughter of his son Elijah, who had married Leonora Chapman.

The widow Elliston left Burlington from 1870 until the 1880s. A house at 52 N High (6th Avenue) was home not only to Elizabeth but also to the Bufords and Farrells, according to the 1880 census. Elliston descendants believe that Elijah took over Burlington for his own use. It was not until 1875 that Elizabeth bought her share of the town house, while G.M. Fogg bought the other half. Norman and Josephine Farrell moved in by 1873, and the Bufords by 1876. The year 1881 would see these families back at the old Elliston lands.

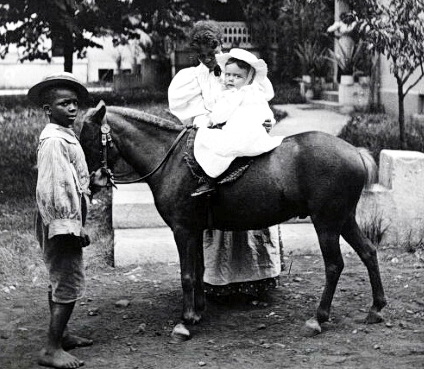

A photo database at the Tennessee State Library and Archives contains numerous images of Burlington as well as of the Ellistons, Bufords, and Farrells. In 1901 the widow Elliston posed for a group photo with her three daughters and some of her grandchildren. Seated next to mother Lizinka Elliston Buford is ten-year-old Eddie Buford, who would go on to become Nashville’s WWI flying ace.

Burlington was not destined to see the Second World War. The mansion was torn down in 1931, and Father Ryan High School, which has since relocated, went up on the site the next year. A part of the original house was saved and reconstructed on Abbott-Martin Road by Ed Buford’s daughter Elizabeth Shepherd, who died in 1955.

Land will pass from one owner to another, buildings will be torn down and new ones constructed, names will be forgotten, and stories will be embellished over time. Through all that, the Ellistons have maintained a place in history, and the importance of that family is witnessed today by a well-known Nashville street–Elliston Place.

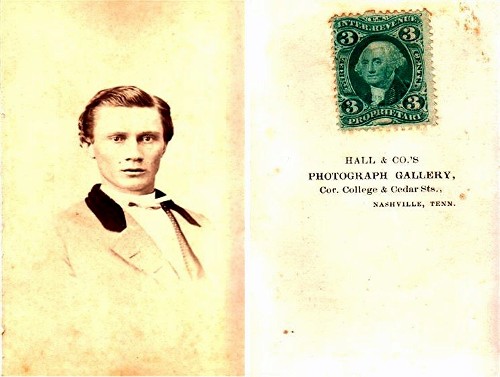

Author’s note: We were never positive that the paper picture used here, taken from a carte-de-visite, was really Lizinka, but based on the two known images of her at the Tennessee State Library and Archives, I’d say the odds are pretty good. This one was taken by C. C. Giers at his Union Avenue studio around 1875, the year Lizinka married Ed Buford. The address on the Giers logo on the reverse side can be shown by city directories to date to 1872-1877.