by Kathy B. Lauder.

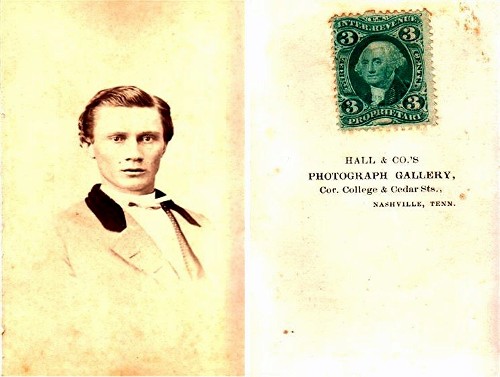

Most authorities agree that George Woods and his brother Joseph were the first African American archaeological field technicians in Tennessee,1 if not the nation. George Woods (born into slavery in March 1842)2 also became the first African American to supervise important mound excavations.

When Frederic Ward Putnam (1839-1915), curator of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology for 34 years,3 came to Nashville in 1877 for a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, he stayed on to explore several important archaeological sites in Davidson and Wilson counties.4 Before returning to Harvard, Putnam employed railroad construction contractor Edwin Curtiss5 as his foreman for the Peabody digs; Curtiss hired the laborers, including, in 1878,6 brothers George and Joe Woods, the only two workmen mentioned by name in his extensive correspondence with Putnam. The Woods brothers rapidly earned a reputation for skill and reliability. Writing from an Arkansas dig, Curtiss complained that the available field hands were “not worth feeding . . . I can get two old hands that have been with me for two years in Nashville and do more with them than I can with 5 of those here and be sure of them every day.”7

After Curtiss’s sudden death in December 1880,8 George Woods wrote to Professor Putnam about continuing Harvard’s archaeological efforts in Tennessee. His letter initiated an interesting correspondence, its principals being one of America’s most prominent scientists and a working-class black man whose nearly illegible handwriting featured his own creative spelling.9 In one letter he mentioned some artifacts remaining at the Jarman dig, explaining that he would return to pick up “thos spesmints that I laft thir in Decbur”10 in order to pack them up for shipment to the Peabody.

During the 1882 and 1883 seasons,11 Putnam hired Woods as foreman on the Jarman Farm site12 (sometimes called the Brentwood Library site) in Williamson County, where archaeologists have classified many outstanding examples of Mississippian culture (700 – ca.1600 A.D.),13 including pots, bowls, and both human and animal effigies. Later Putnam placed Woods in charge of the John Owen Hunt Mound dig in Williamson County while still collecting artifacts from the Jarman and Hunt excavations, as well as Dr. Oscar Noel’s farm/cemetery in Davidson County and Judge William F. Cooper’s farm, “Riverside,” in East Nashville near the McGavock Pike ferry landing.

Woods ended his association with Putnam about 1884, but continued to work at Middle Tennessee sites with “local antiquarian archaeologist”14 Gates P. Thruston from 1885-1890. In the Gates P. Thruston Collection of Vanderbilt University, now housed at the Tennessee State Museum,15 may be found several artifacts collected by George Woods,16 who, in later years, worked as a blacksmith, railroad porter, and quarryman.

George Woods, who died January 26, 1912,17 is memorialized on Tennessee Historical Commission marker #3A 217 near the entrance to Greenwood Cemetery, where he is buried.18

Note: Several sources give Woods’s death date as September 28, 1912, but both the Tennessee Death Records, 1908-1958, and the Tennessee, Deaths and Burials Index, 1874-1955, cite the January date, which is listed on his death certificate. (2015)

SOURCES:

1 Moore, Michael C., and Kevin E. Smith. “Archaeological Expeditions of the Peabody Museum in Middle Tennessee, 1877-1884.” Nashville: TN Department of Environment & Conservation, Division of Archaeology, Research Series No. 16, (rev. 2012), 8. https://www.tn.gov/environment/docs/arch_rs16_peabody_museum_2009.pdf

2 Moore, Michael C., Kevin E. Smith, and Stephen T. Rogers. “Middle Tennessee Archaeology and the Enigma of George Woods.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. LXIX, Number 4 (2010), 321.

3 Tozzer, Alfred M. Biographical Memoir of Frederic Ward Putnam, 1839-1915, Vol XVI, No. 4. National Academy of Sciences: Presented to the Academy at the annual meeting, 1933, 127.

4 Moore, Michael C., et al. “Middle Tennessee Archaeology,” 320.

5 Browman, David L., and Stephen Williams. Anthropology at Harvard. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2013, 105.

6 Browman and Williams, 105.

7 Moore and Smith. “Archaeological Expeditions,” 8.

8 Moore and Smith, “Archaeological Expeditions,” 5.

9 Moore, Michael C., et al. “Middle Tennessee Archaeology,” 323.

10 Moore, Michael C., et al. “Middle Tennessee Archaeology,” 323.

11 Browman and Williams, 106.

12 Putnam, F. W. “Abstract from the Records,” February 18, 1884. Annual Report of the Trustees of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Volume 3. Boston, Massachusetts: John Wilson and Son, 1887, 351.

13 “Mississippian Culture: Ancient North American Culture.” Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., n.d. Web. (Accessed 10 May 2015) http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/385694/Mississippian-culture

14 “George Woods, 1842-1912.” Tennessee Historical Commission Marker #3a 217, on north side of Elm Hill Pike between Spence Lane and entrance to Greenwood Cemetery.

15 Smith, Kevin E. “Gates P. Thruston Collection of Vanderbilt University.” Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society. Online Edition ã 2002-2015, The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, Tennessee.

16 Moore, Michael C., et al. “Middle Tennessee Archaeology,” 324.

17 Tennessee Death Records, 1908-1958, Roll #5. Nashville: Tennessee State Library and Archives.

18 “George Woods, 1842-1912.” Tennessee Historical Commission Marker #3a 217.

SUGGESTED READING:

Moore, Michael C. The Brentwood Library Site (A Mississippian Town on the Little Harpeth River, Williamson County, Tennessee). Tennessee Division of Archaeology Research Series (Book 15). Nashville: Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, 2005.

Moore, Michael C., Kevin E. Smith, and Stephen T. Rogers. “Middle Tennessee Archaeology and the Enigma of George Woods.” Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. LXIX, Number 4 (2010), pp. 320-329.

Smith, Kevin E., and James V. Miller. Speaking with the Ancestors: Mississippian Stone Statuary of the Tennessee-Cumberland Region. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2009.