by Doris Boyce.

A detail in the death of a Williamson County Civil War hero was clarified after Colonel William Shy’s grave was vandalized in 1977. Before that time, it was believed that Shy had been killed by a mini-ball shot from a muzzle-loading firearm during the Battle of Nashville, December 16, 1864. When anthropologist Dr. William M. Bass (founder of the University of Tennessee’s “Body Farm”) reconstructed the wound in Shy’s skull, he found that the wound was too large to have been caused by a mini-ball. Shy’s wound was more likely the result of the bombardment that Nashville citizens had watched from Capitol Hill.

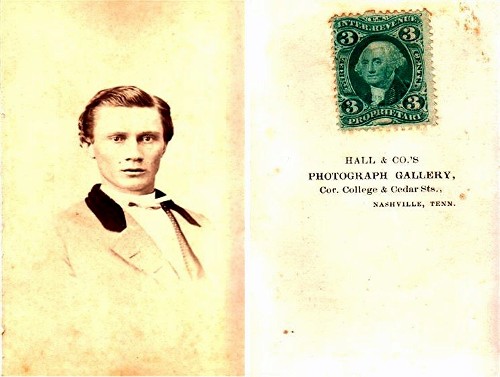

William Mabry Shy, Colonel of the 20th Tennessee, was left dead on the top of what was then Compton Hill. When his body was recovered, it had been stripped and bayoneted to a tree. His descendants are still in possession of the bayonet. General Benton Smith*, Shy’s superior officer, was taken prisoner at the bottom of the hill, where his captor cracked him over the head three or four times with a saber. He never entirely recovered and ended his life in an insane asylum.

General John Bell Hood, Confederate commander of the battle, appeared to associate valor with casualties. Hood was a none-too-stable combat veteran who had to be tied onto his horse because of a useless arm and an amputated leg. Sixteen days earlier, on November 30th, Hood had attacked the Union Army in the bloody one-day Battle of Franklin, which had resulted in 6,000 Confederate losses.

The Battle of Nashville thrust 21,000 of Hood’s ill-equipped infantry and 4,000 cavalry against General George H. Thomas’s well-equipped Union infantry, about 60,000 strong. The fighting took place in the hills near the present-day intersection of Granny White Pike and Harding Place/Battery Lane, ultimately spreading over five miles, from Franklin Road to Hillsboro Pike. The Union bombardment lasted for two days before their troops attacked with overwhelming force. Confederate survivors limped away as best they could after suffering some 4,000 casualties. After the Battle of Nashville, Hood, a West Point graduate who believed in frontal attacks with flags flying, retreated to Mississippi. In January of 1865, less than one month later, he gave up command, having all but destroyed the Army of Tennessee. Hood died in relative obscurity after ten years as a successful New Orleans businessman.

Thankfully, the valor of the Confederate dead will not be forgotten. In 1968 the Metro Historical Commission placed a plaque at the slope of Compton Hill, which has been re-named Shy’s Hill. The area can be accessed via Shy’s Hill Road or Benton Smith Road from Harding Place, two blocks west of Granny White Pike.

* Gen. Thomas Benton Smith, who had been gravely wounded at Stones River (31 Dec 1862-2 Jan 1863) and Chickamauga (18-20 Sep 1863), returned to military duty after his eventual recovery. As Smith surrendered to Union Col. William L. McMillen during the Battle of Nashville, McMillen attacked the disarmed general savagely with his own sword, causing such severe brain injuries that Smith was at first not expected to survive. Although he eventually recovered sufficiently to return to his pre-war job at the Nashville & Decatur Railroad, he was eventually confined in a Nashville insane asylum, where he lived for most of his last 47 years. He is buried in Confederate Circle at Mt. Olivet Cemetery.

Editor’s note: When this essay was published earlier on another site, a reader strenuously objected to its characterization of General John Bell Hood. We understand that other views of Hood’s tactical wisdom and effectiveness are certainly possible. Hood was a complex individual whose actions have engendered both hostility and admiration among those who have studied his military career. The points of view expressed in this essay are those of its author, but other positions may be equally valid. We encourage any reader to submit an essay detailing your own perspectives on Hood, particularly as they relate to the Battle of Nashville.