by Kathy B. Lauder.

We would be remiss if we neglected to mention some of the quiet heroes who provided support to the protests with their time, money, and encouragement. Among the most generous were two Nashville couples – Dr. Charles and Mary Celeste Richardson Walker, and Dr. McDonald and Jamye Coleman Williams.

Georgia native Charles Julian Walker (1912-1997) earned his M.D. from Meharry in 1943 and opened a medical office in Nashville four years later. So devoted was he to his practice, he once agreed to see a patient when he was hospitalized himself! Deeply committed to the civil rights movement, he worked tirelessly behind the scenes, pressuring local leaders to take immediate action after the bombings of Hattie Cotton School (1957) and the Looby home (1960). He and his wife also quietly posted bail for many of the students arrested during the sit-ins. Walker served briefly in the Tennessee House after being appointed to fill a vacancy in his district, and he was a Fisk University trustee during the 1970s, encouraging the university to become more accountable to the community. According to his longtime friend, Tennessee Supreme Court Chief Justice Adolpho A. Birch, he was “fierce” and relentless in urging politicians and businessmen to invest in struggling low-income communities and to expand and diversify the work force. An outspoken champion of prison reform, he was a tireless advocate for prisoners’ rights. Although Dr. Walker was known for his energy and optimism, the loss of his beloved wife Mary in 1994 sent him into a downward spiral from which he never fully recovered.

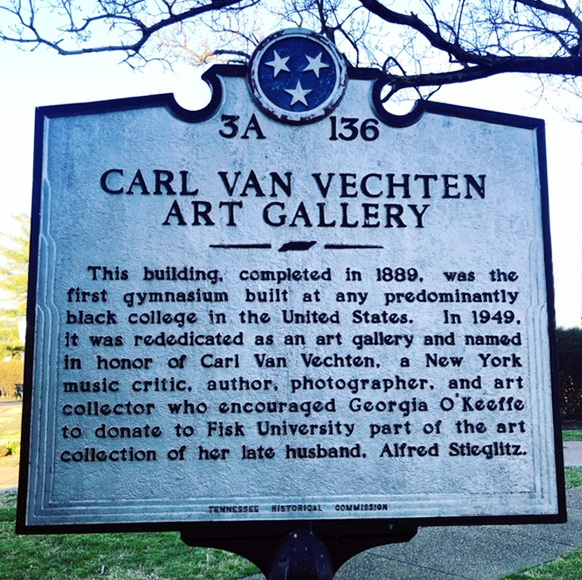

Mary Celeste Richardson Walker (1910-1994) demonstrated a lifelong concern for social justice. Her parents divorced when she was a toddler, and she grew up in the home of her grandparents, Fire Captain Reuben B. Richardson and his wife. She attended Nashville city schools and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Fisk University. When Dr. C.J. Walker met her in early 1942, he was immediately smitten. The Meharry graduate promptly proposed, and the couple married, as Walker liked to say, “five weeks after I first laid eyes on her.” That fall Mary began a 30-year career teaching English at Pearl High School, where she earned a reputation for being tough but fair, showing particular concern for disadvantaged and at-risk students. She and her husband shared a strong commitment to supporting the young civil rights demonstrators in Nashville, providing generous financial and moral support to the movement. Shortly after Mary retired from teaching, Governor Lamar Alexander appointed her to the state parole board, where her even-handed approach to the situations they faced won the profound respect of both inmates and judicial authorities. A member of Church Women United, educational advisory boards, and other civic organizations, she was a trustee of Scarritt College, as well as a lifetime member of the NAACP.

A native of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, McDonald Williams (1917-2019) came to Nashville with his wife Jamye Coleman Williams in 1958, he as an English professor specializing in 19th century English literature, and she as chair of the Tennessee State University Communications Department. When TSU initiated its Honors Program in 1964, Mac Williams was appointed director, serving in that position until his retirement in 1988. Together the couple edited the A.M.E. Church Review and The Negro Speaks: The Rhetoric of Contemporary Black Leaders, and they provided valuable support to Nashville’s civil rights activities. The Williamses received many awards for their service, including the Otis L. Floyd Jr. Award from Saint Bernard Academy, the Joe Kraft Humanitarian Award from the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee, and the Human Relations Award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews. In 1995 a room in the newly remodeled Northwest YMCA building was dedicated to Dr. Williams, a longtime board member. He died in Atlanta at age 101.

The daughter of a Kentucky minister, Jayme Coleman (1918-2022) earned a B.A. with honors from Wilberforce University at age 19 and an M.A. from Fisk the following year. She taught English at Wilberforce and three other HBCUs before earning a doctorate in speech communications at Ohio State University. In 1959 she began teaching at Tennessee State University, and she was named department head in 1973. She and her husband, educator McDonald Williams, were valuable organizers and supporters of the Nashville sit-in movement, later playing an active role in the development of the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee, where their efforts earned them the Joe Kraft Humanitarian Award of the CFMT in 2002. A lifelong member of the A.M.E. Church, Jamye Williams was a member of the board of the United Council of Churches, president of the 13th District Lay Organization, and editor of the AME Church Review, the oldest African American literary journal. A member of the NAACP Executive Committee, she received the organization’s Presidential Award in 1999. She lived to be 103 years old.

You might enjoy these two short video clips of an interview with McDonald and Jamye Coleman Williams: A. and B.

Some of this material has been adapted from the Greenwood Project.

Important books about the Civil Rights Movement in Nashville:

- John Egerton: Speak Now Against the Day: The Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South (winner of the Robert F. Kennedy Book Award)

- David Halberstam: The Children

- John Lewis: Walking with the Wind

- Bobby L. Lovett: The Civil Rights Movement in Tennessee