by Kathy B. Lauder.

“A good coach can change a game. A great coach can change a life.” John Wooden

WALTER STROTHER DAVIS (August 9, 1905 – October 17, 1979) was born in Canton, Mississippi. After receiving a B.S. from Tennessee A&I (now Tennessee State University), he earned his M.S. (1933) and Ph.D. (1941) from Cornell University. Before completing his doctorate, Davis was employed by TSU in 1933 as head football coach and professor of agriculture. Within ten years he had earned his Ph.D. and was elected the school’s second president, serving in that role for twenty-five years (1943-1968). Under his leadership, university enrollment grew from 1,000-6,000 students. During that same period the school gained university status (1951), constructed 24 new buildings, and established six new schools: Arts & Sciences, Education, Engineering, Agriculture, Home Economics, and a graduate school. In 1958 TSU achieved land-grant status and was also awarded accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. Davis proved his commitment to athletic excellence by hiring superior football coaches like John Merritt and Joe Gilliam Sr., along with other great leaders. Davis retired in 1968 and was named to the TSU Hall of Fame in 1983.

Another notable achiever Walter S. Davis brought to Tennessee State University was legendary track coach ED TEMPLE, whose talents attracted dozens of stellar athletes to the school. Temple headed the TSU women’s track and field program for 44 years, during which time his Tigerbelles won 23 Olympic medals. Among the 40 Olympic athletes Temple trained were gold medalists Wilma Rudolph (1960 – a former polio patient who became the first American woman to win three gold medals in the same Olympics), Wyomia Tyus (1964 & 1968 – the first person, male or female, to retain the Olympic 100-meter title), and Ralph Boston (1960 – the first man to top 27 feet in the long jump). In addition to their international successes, Ed Temple’s athletes held over 30 national titles. The U.S. Olympic Committee called him “the most prolific women’s track and field coach in the history of the sport.”

JOHN AYERS MERRITT (January 26, 1926 – December 15, 1983) was a Kentucky native who moved in with an aunt in order to play football at Louisville’s Central High School. After graduation he enlisted in the U.S. Navy, but when he returned, he won a football scholarship to Kentucky State College. He graduated in 1950 and went on to graduate school at the University of Kentucky, earning his M.A. in 1952. Merritt spent ten years coaching football at Mississippi’s Jackson State University (1952-1962) before Walter S. Davis hired him to be head football coach at Tennessee State University. He moved to Nashville in 1963, bringing along his talented assistants, Joe Gilliam Sr. and Alvin Coleman. Merritt’s career included thirty straight winning seasons, four undefeated seasons, and an NCAA 1-AA playoff victory in 1982. By the time ill health led to his retirement at the end of the 1982-1983 season, he had amassed a cumulative coaching record of 233-67-11. During his long career he coached 23 future NFL players, including six who played on Super Bowl teams. He died less than a year after retiring and in 1994 was inducted posthumously into the College Football Hall of Fame. In 1995 Merritt received the American Football Coaches Association’s Amos Alonzo Stagg Award, presented annually to an “individual, group, or institution whose services have been outstanding in the advancement of the best interests of football.”

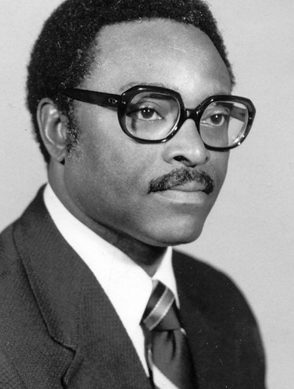

John Merritt’s able assistant, JOSEPH W. “COACH” GILLIAM SR. (March 26, 1927 – November 14, 2012) had been an All-American quarterback at West Virginia State University. After graduation he coached football and basketball at Oliver High School in Winchester, Kentucky (1952-1954), leading them to a state football championship in 1954 and winning the title of Kentucky High School Football Association Coach of the Year. The following year he joined John A. Merritt’s coaching staff at Jackson State in Mississippi, where the team won a national championship. Gilliam left Mississippi in 1957 to become head coach at Kentucky State, but, having compiled a fairly unimpressive record there, he soon followed Merritt to Tennessee State (1963) as defensive coordinator. During the next 20 years the Merritt-Gilliam combo led the Tigers to four undefeated seasons and seven national titles. Gilliam himself served as head coach at TSU from 1989-1992 and was named Ohio Valley Conference Coach of the Year in 1990. He was inducted into the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame in 2007. His son, “Jefferson Street Joe” Gilliam (1950-2000) was the starting quarterback at Pearl High School during Nashville’s first season of integrated football. He developed into a football standout at Tennessee State University, was drafted by the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1972, and, after taking the field as starting quarterback in the first six games of the 1974 season, gained recognition as one of the first black quarterbacks ever to start an NFL game.

RONALD R. “Scat” LAWSON SR. (April 26, 1941 – February 6, 2002) was the son of James R. Lawson, Fisk University president from 1967 to 1975, and Lillian Arceneaux Lawson. Young Ronnie attended Father Ryan High School his freshman year (1956-57), but, because its athletic teams were not yet integrated, transferred to Pearl High School in 1957 in order to play basketball under Coach William Gupton. The Pearl Tigers won the Black National High School Championship Lawson’s junior and senior years. Offered basketball scholarships to several universities, Lawson chose UCLA in order to play for Coach John Wooden. The youngster set freshman scoring and rebounding records that stood for six years (until they were broken by freshman Lou Alcindor, better known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), and he was named Honorable Mention All-American his sophomore year. In 1962 he transferred to Fisk, earning his B.A in 1963 and his M.A. in 1966. Lawson was hired as head coach of Cameron High School in 1964, while its student body was still entirely African American. He led the school to state championships in 1970 and 1971, with a 61-1 two-season record. After Cameron closed in 1971 and its students were sent to McGavock High School in Donelson, Lawson served as head coach of the Fisk men’s basketball program. He was a 2004 selection of the TSSAA Hall of Fame.

JELANI KHALIB OVERTON (December 11, 1980 – November 15, 2008) first appeared in local sports pages (1994) as one of Joelton’s eighth-grade football “players to watch” By 1998 he had earned area-wide recognition as an All-Region Football offensive lineman. Graduating from Whites Creek High School (1999), he enrolled at Tennessee State University, where he played football, earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and even taught a few courses himself. His first job working for Metro Schools was to teach physical education at Napier Elementary School. A short time later he began coaching football, first at Stratford High School and then at Hillwood, where he became a beloved member of the school community. Other Nashvillians got to know the generous and supportive young man through his part-time job at the Northwest YMCA. In March 2008 Jelani’s students and friends were horrified to learn that he had been diagnosed with cancer. The disease took him quickly: only 27 years old, he died eight months after his diagnosis. Hillwood High School, devastated by his loss, named its annual senior athletic retreat in his honor. But even more gratifying were the memorial tributes from his players, whose lives he had clearly touched very deeply: “You were the greatest coach, mentor, and friend I could ever ask for” . . . “I’m doing my best to make you proud” . . . “I thought about what you said and I didn’t drop out I stayd in school” . . . “Im gon keep you alive by doin the right thing.”

Adapted from essays in the Greenwood Project.