by Lewis L. Laska.

This is the story of the most famous execution in Nashville history and how it led to the deaths of four young men – the Hefferman killers – within months. It is evidence of how violence begets violence, a story that is much older than Nashville. It begins with the death of Champ Ferguson.

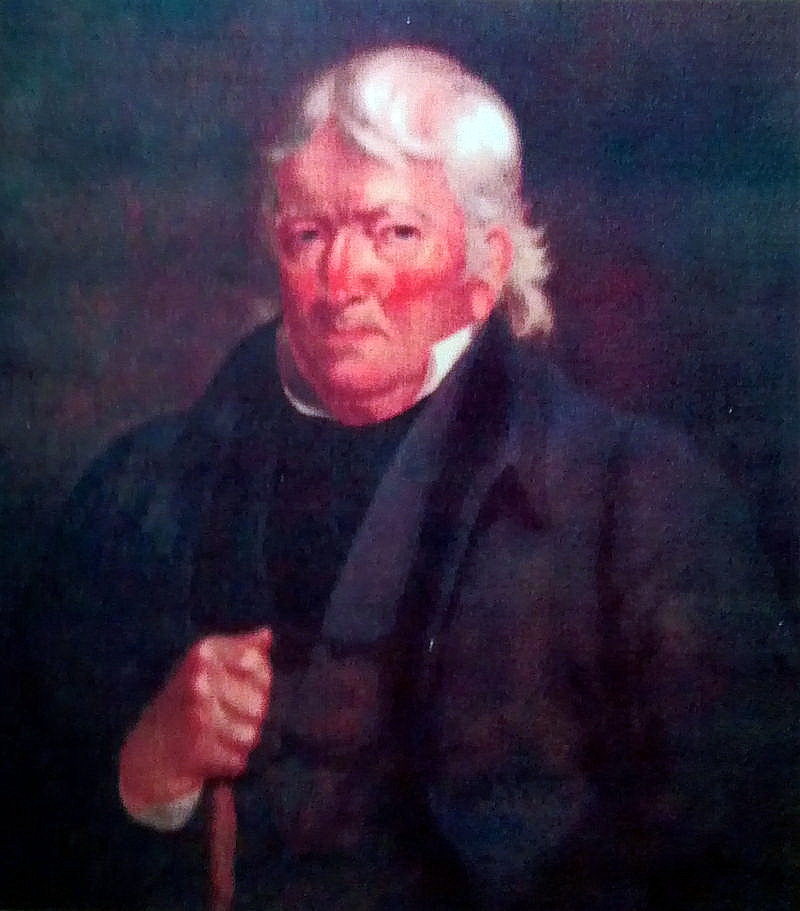

This legendary execution occurred on October 20, 1865, as a result of the Civil War. Champ Ferguson was a Confederate guerilla. Captain Ferguson, as he was sometimes called, had assembled a band of killers that preyed on Union soldiers and partisans in the upper Cumberland area. By the time the war ended, Ferguson boasted of killing over a hundred men.

Union authorities refused to recognize his purported military status and arrested him for murder on May 26,1865.1 Most of the killings occurred in southern Kentucky, but the prosecution was not based on a formal investigation. Instead, when news circulated that Ferguson was to be charged, his victims’ families besieged federal authorities with stories of atrocities, and scores of them eagerly traveled to Nashville for his trial.

Because he was charged with murder, Champ Ferguson was brought before a military commission, which was neither a civil court nor a court-martial. This system had been used throughout the Civil War to bring criminals to justice. It was the same sort of commission that had sent Sam Davis to the gallows for spying in 1863. On the very day Ferguson was arrested, the four Lincoln Conspirators were executed at the nation’s capital after being tried and convicted by a military commission.

Ferguson came before a six-member commission in July 1865, and his trial lasted until September.2 Twenty-three specific charges were brought against Ferguson, who was accused of murdering fifty-three men. According to witnesses, he simply shot people dead, sometimes in their own homes in front of their wives and children.

Among the victims was Reuben Wood (white, age unknown), who had known Ferguson as a child. Ferguson and two other men rode to Wood’s house near Albany, Kentucky, on December 2, 1861, and inquired whether Wood had been to a Union mustering ground at Camp Dick Robinson. Hearing that he had, Ferguson cursed him, called him a “damned Lincolnite,” and shot him in the chest with a pistol in front of Wood’s adult daughter.3

Ferguson insisted that Wood was a member of a Union partisan gang who had been issued shoot-to-kill orders for Ferguson. “If I had not shot Reuben Wood, I would not likely have been here, for he would have shot me. I never expressed a regret for committing the act, and never will. He was in open war against me.”4 Contemporary Southern writers refused to condemn Ferguson’s actions, insisting they were no different from those of equally bloodthirsty Union guerillas like the infamous Tinker Dave Beaty, who operated in the same area.5

Ferguson was also charged with murdering Alex Huff in Fentress County in 1862, and with killing David Delk by chopping and cutting him to pieces at the Fentress County home of Mrs. Alex Huff in 1863. Other charges included slaying nineteen soldiers of the 5th Tennessee Cavalry (names unknown), on February 22, 1862.6 Elijah Kogier was shot at his home in Clinton County, Kentucky, in 1862 as his little daughter clung to him, pleading for his life. In 1861 Ferguson killed William Fogg, who was sick in bed and did the same to Peter Zachery at Rufus Dowdy’s house in Russell County, Kentucky, in January 1863.

Ferguson’s most notorious murder occurred in Emory, Virginia, on November 7, 1864.7 Marching into a Confederate hospital, he strode to the bed of a Union officer known only as Lt. Smith. Brandishing a pistol, Ferguson announced he was going to kill Smith and promptly shot a bullet into the man’s brain. It was this particular killing that led to Ferguson’s arrest. He was held for court-martial by the Confederate army, but he was released because the Confederate forces were too disorganized by that point in the war to follow through. At his trial Ferguson was mute regarding Lt. Smith, but his defense to the other murders was simply that he killed people who were trying to kill him, if they had the chance.

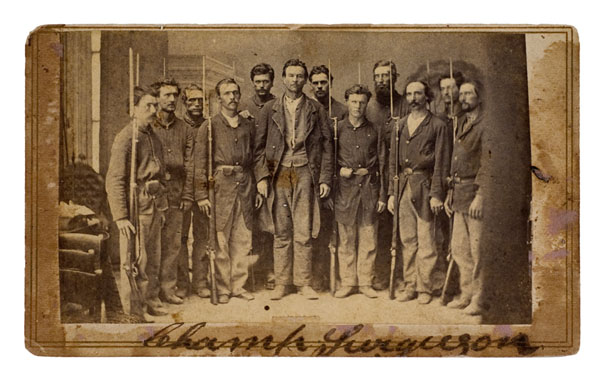

Regarding Lt. Smith, Ferguson spoke freely after his trial ended. “I acknowledge that I killed Lt. Smith in Emory and Henry Hospital. I had a motive in committing the act. He captured a number of my men at different times, and always killed the last one of them. I was instigated to kill him, but I will not say by whom, as I do not wish to criminate my friends. [Smith] is the only man I killed at or near Saltville [a battle that sent Smith to the hospital], and I am not sorry for killing him.”8 Because of Ferguson’s notoriety, a number of his guards contrived to have their picture taken with him, and several of those images survive. The trial received daily verbatim newspaper coverage.

Ferguson’s chief defense was that his actions fell within the terms of the surrender which barred punishment for actions committed during the war. His lawyers had convinced former Confederate General “Fighting Joe” Wheeler to attend. Wheeler’s testimony was generally favorable to the defense but failed to establish clear evidence that Ferguson had held a commission or had received and obeyed orders in killing any of the persons named in the indictment.9

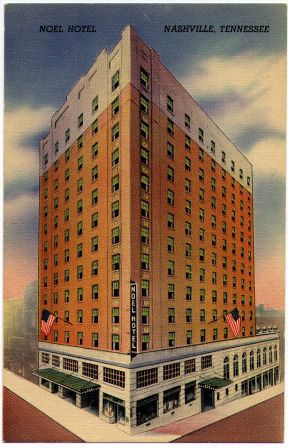

The military commission convicted Ferguson in September, and he was hanged October 20, 1865, at the Nashville prison on Church Street, in front of three hundred people who had received passes to witness his death. The prison itself was protected by soldiers from the 15th United States Colored Infantry, a circumstance that greatly irritated the townsfolk.

As the long sentence was being read to Ferguson on the gallows, he alternately nodded and shook his head at various charges. When the Colonel said, “to all which the accused pleads not guilty,” Ferguson said, “But I don’t now!” After the cap was placed, he called out in a loud voice, “Oh, Lord, have mercy on me!”10

Champ Ferguson’s execution started a folklore tradition that endured for decades, namely that he was not actually hanged, but that his body was spirited away in a coffin and given to his wife and teenage daughter who had been present but unnoticed at his execution.

The folklore arose out of the fact that supposedly no one actually saw Ferguson’s body hanging after it dropped. The area below the gallows was obscured by wooden planking; hence, he might conceivably have been placed in his coffin alive. Indeed, the widely seen drawing of his execution – found in Harper’s Weekly, November 11, 1865, at page 716, shows it was impossible to see the gallows bottom, although the image shows Ferguson hanging.

One folklore tradition holds that Ferguson’s pillaging during the war made him wealthy, so his wife had the means to bribe the hangmen into placing the body of a recently deceased (supposedly hanged) black man in the coffin.11 Another version says that rocks were placed in his coffin, which was nailed shut when his wife carried it away.

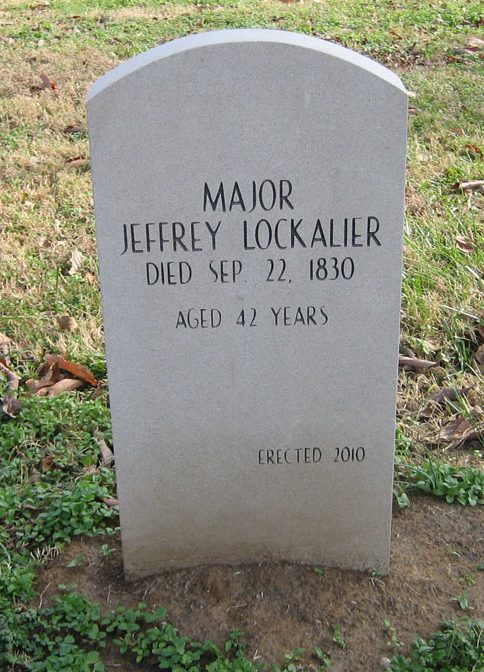

The folklore is further enhanced because his wife and daughter left Tennessee for the West and were never heard from again – and by the fact that Ferguson’s name was misspelled on his gravestone. The story of Ferguson’s “escape” was retold every time a man was hanged in late 19th-century Tennessee. For this reason, hanged men’s bodies were often placed in an open coffin near the jail or place of execution for all to see.

The execution of Champ Ferguson probably led to the execution of George Crabb, James Lysaught, Thomas Perry, and James Knight. All were white. All except Knight, age 20, were teenagers. And despite their ages, all had criminal records.

Crabb was prosecuted and executed under the name “George Craft.”12 He had used the alias “Reid” or “Red.” Perry was sometimes known as “Ferry.” Knight had used the alias “McClusky” and was arrested under that name, but he also used the alias “William Dran” or “Dean.” He was prosecuted and executed as William Dean. Lysaught’s name has been reported as “Lycought.” These young men were known as the Hefferman killers.

Their crime was committed on the night of November 22, 1865, when Nashville was still under federal control. The killers were civilians employed as hands in the Army corrals. Knight had served in Confederate service in an Arkansas regiment. Perry had served in the 11th Tennessee and claimed to have been among those captured at Ft. Donelson. Crabb had been a teamster in the 11th Army Corps under Gen. Joseph Hooker. The killers lived in the back of a low saloon (referred to as a “doggery”) on Jefferson Street, then occupied by federal soldiers of both races.

William Hefferman (sometimes spelled “Heffran,” “Heffernan,” “Hufferman”), white, age 60, was a wealthy and respected street and railway contractor. Hefferman, his wife, adult daughter, and her husband Mr. Tracy, were returning to their home from a musical program at St. Cecilia Convent.

As the Hefferman carriage came near the doggery, four to six young men came out and suddenly turned toward them. Perry stopped the horse. Mr. Tracy asked, “What do you want!” as Hefferman said, “Surely you don’t mean to hurt anyone here!” Perry, closest to Hefferman, said, “Yes, goddamned quick, if you don’t give up your money!” Hefferman replied, “I am a private citizen, near my own home, just from an evening party and have no money.”13 Crabb seized Hefferman, pulled him to the ground, and beat him with a Billy club. Mrs. Hefferman got out to help her injured husband.

At that moment, Mr. Tracy shot a pistol at Crabb, and the bullet struck a glancing blow at the nipple and exited the chest. Crabb returned fire. His bullet grazed Mrs. Hefferman’s face and entered her husband’s nose, passing into his skull. The buggy bolted, still carrying the Tracys. By the time Mr. Tracy was able to control it, the killers had escaped. Taken to his home, Hefferman was able to describe both the incident and the killers, although he was bleeding badly and brain matter was coming out his nose. Hefferman died on November 26.

News of the incident stunned the city, and the next day two prostitutes led the town marshal to the injured Crabb, who quickly confessed and implicated the others. Perry had escaped to Murfreesboro, where he was arrested after breaking into a shed.14

Taken to jail, Crabb and his accomplices were visited by East Tennessee Unionists, Gen. Brownlow and Col. Horace Maynard. They identified Crabb as the person who had robbed them a few days earlier on the Franklin turnpike.

A three-member military tribunal heard evidence against all but Perry in November; Perry’s trial began on December 3, 1865. Co-defendant Joseph A. Jones (alias “Tom Carter”) denied involvement. Perry insisted he had not actually stopped the horse, only stood in front of it. He said Crabb was the shooter. Witnesses included persons the killers had confided in, such as Perry’s supervisor at the corral, who said that Perry had told him the details of the crime, which he relayed to the tribunal.15

All but Jones were found guilty of a multiple-count indictment and sentenced to death by hanging.16 They appealed to Gen. Thomas, who rejected their appeal on January 16, 1866. He sent the case to General Grant. Grant, too, refused them, as did President Andrew Johnson.

Throughout the trial and the appeal, the defendants maintained a confident and defiant manner, convinced they would be granted clemency. They broke only briefly, but generally maintained bravado, including joking, up to the moment they were pinioned and taken to the scaffold.17 Then they began to tremble and sob.

The killers were seated on coffins and taken to the gallows on two wagons, each pulled by four white horses. The execution was carried out on January 26, 1866, at the state prison on Nashville’s Church Street and was witnessed by a solemn and orderly crowd of ten thousand. Knight exhorted the on-lookers, “I wish to say to all, don’t swear, don’t visit low houses, don’t gamble, don’t do anything wrong. If you take warning by me, you will never meet my fate, but I am going to a better world.”18

Lysaught, the youngest, who had earlier joked that he weighed so little he might not actually die by the hanging, said, “I am no scholar; I have no education, but I wish, gentlemen, to say, that I hope I am going to a better world. I forgive everybody, and I hope no man in this crowd has anything against me; if he has, I hope he will forgive me.” After thanking the military jailers for treating him kindly, and stating that if he had stayed in the city jail he would have starved to death, Lysaught concluded, “That is all, gentlemen, I am going to a better world and I hope to meet you all there.”19 Each bid the other farewell as the caps were being drawn over their heads.

Lysaught’s neck was broken; the other three were strangled, notably Perry. The knot had slipped around the back of his neck. The killers were buried in unmarked graves at the National Cemetery in Nashville.

Later in 1866 the United States Supreme Court ruled that criminal trials by military commissions were unconstitutional where the state courts were open, as they were in Nashville at this time.20 But the result was not likely to have been different.

At the time of the Hefferman murder, in November 1865, the military was still trying to keep the peace in Middle Tennessee. The media carried frequent accounts of gangs robbing civilians.21 Most of the gangs were garbed in at least partial blue uniforms. The execution of the Hefferman killers was a signal that the Army would punish federal lawbreakers as well as former Confederate killers like Champ Ferguson. Coming on the heels of the Ferguson execution, it showed fairness to all, regardless of prior allegiance. This was the first quadruple execution in Tennessee. It would not be the last.

Notes:

1 Thurman Sensing. Champ Ferguson, Confederate Guerilla. (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1942), p. 1. (Standard biography of Ferguson.) See, J.D. Hale. Sketches of Scenes in the Career of Champ Ferguson, His Lieutenant, With Champ’s Confession, J. M. Hughes and the K.K.K. (The author: Hale’s Mills, Tennessee, no date [circa 1867]. 54 pp.

2 One of Ferguson’s lawyers was Josephus C. Guild, later a judge and dean of the Nashville bar. He vigorously defended Ferguson, but wrote nothing about the case in his memoirs except this: “October 20, 1865, Champ Ferguson was hung at the penitentiary on account of war operations. On the 20th of November William Heffran was dragged from his carriage and murdered by some ruffians belonging to the Federal army, who were subsequently apprehended, tried by a court-martial, convicted, and hung. The execution took place January 26, 1866.” Josephus C. Guild. Old Times in Tennessee. (Nashville: Tavel, Eastman & Howell, 1878) p. 496.

3 Id., note 1, at p. 83-84.

4 Id., note 1, at p. 87.

5 Bromfield L. Ridley. Battles and Sketches of the Army of Tennessee. (Nashville: 1906). (Ridley served on Gen. A. P. Stewart’s staff.)

6 Id., note 1, at p. 29.

7 Id., note 1, at p. 177.

8 Id., note 1, at p. 188.

9 Id., note 1, at p. 208-216. At 5′ 2″ tall, Wheeler was known as “Little Joe” Wheeler during the war, but became “Fighting Joe” thereafter. He was placed in command of the cavalry of the Army of Tennessee in 1862. Sothrons saw his testimony at Ferguson’s trial as a courageous gesture. By the time of the Spanish-American War, Wheeler “went over” to the Federal Army and was named a general, a largely symbolic gesture, but an important one.

10 See “From the Nashville Daily Press and Times, October 21, 1865,” in August Mencken. By the Neck: A Book of Hangings. (New York: Hastings House, 1942) at p. 120-126.

11 “Champ Ferguson,” Daily American, September 28, 1879, p. 2. In publishing the tale, this newspaper says that Ferguson was seen hanging by Henry Watterson, who wrote about it when he was a reporter for the Republican Banner. He was currently editor of the Louisville Courier-Journal.

12 “Fate of the Hefferman Murderers,” Nashville Union and American, Jan. 18, 1866, p. 1.

13 “Murder, Melancholy Progress of Highway Robbery in the State Capitol,” Republican Banner, November 24, 1865, p. 2.

14 “Another Murderer Arrested,” Republican Banner, Dec. 2, 1865, p. 1.

15 “Trial of Thomas Perry,” Republican Banner, Dec. 3, 1865, p. 2.

16 “The Heffernan Murderers,” Nashville Union, Jan. 18, 1866, p. 3. “Interview with the Hefferman Murderers,” Union and American, Jan. 20, 1866, p. 3.

17 “Talk With the Murderers of Heffernan,” Nashville Union, Jan. 25, 1866, p. 2.

18 See Pittsburgh Post (Pittsburgh, Pa.), February 1, 1866.

19 “Execution of the Hufferman Murderers,” Nashville American, January 27, 1866, p. 2.

20 Ex parte Milligan, 71 U.S. 2 (1866).

21 “Highway Robberies on the Murfreesboro Pike,” Republican Banner, December 10, 1865, p. 2. “Another Horrible Murder,” Republican Banner, December 11, 1865, p. 3.